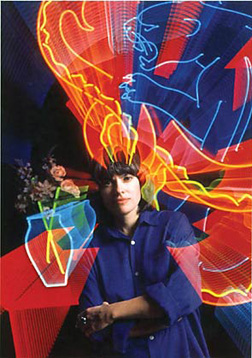

Lili

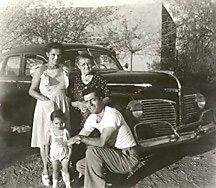

Lakich was born in Washington, D.C., but soon moved to Tucson, Arizona when

her father's military career transfered the family to Davis Monthan Air Base

and then to California when he was sent to the Korean War. "When my father

returned from the Korea," she recalls, "the first thing he did was

buy a brand new, light-blue Chrysler. We drove all over the United States,

visiting relatives and old friends from California to Florida. By day we read

all the clever Burma Shave signs and stopped at every souvenir shop or roadside

attraction that was made to look like a wigwam, teapot or giant hamburger,

but it was driving at night that I loved best. It was then that the darkness

would come alive with brightly colored images of cowboys twirling lassos atop

rearing palominos, sinuous Indians shooting bows and arrows, or huge trucks

in the sky with their wheels of light spinning. These were the neon signs

attempting to lure mororists to stop at a particular motel or truck-stop diner.

We stopped, but it was always the neon signs that I remembered."

She attended six 5th grades and three high

schools in the U.S. and Germany (her father was now stationed in Frankfurt).

After graduating from high school near Fort Meade, Maryland (between Baltimore

and Washington, D.C.), she went to college at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn,

New York. Dissatisfied with the traditional painting, printmaking and sculpture

classes that were offered, she

left Pratt after her second year to attend the London School of Film Technique

in London, England. Filmmaking proved to be too much of a group activity,

so she returned to Pratt and earned a Bachelor Fine Arts degree in 1967.

While at Pratt, a devastating personal relationship

led her to create her first light sculpture, a self-portrait with tiny light

bulbs controlled by a motor, blinking down her face like tears. "This

was my first electric work of art," she says, "and for the first

time in my life, I felt that I had really and absolutely expressed myself.

For me, art is cathartic—-a means of packaging emotion and exorcising

it. Once I had made a portrait of myself crying, I could stop crying. The

sculpture cried for me. If you can express mangled feelings in a work of art,

you can overpower them. They then exist as a set of lines, colors and forms.

They're no longer an amorphous nausea eating away at your gut. They're incoporated

into an object. You can see it. You can hang it on a wall. And if you can

make it beautiful, you can somehow feel that it has sanctity...that it is

an icon capable of arousing an emotional response in other people as well."

Remembering her love of neon

in the landscape, she set out to learn to incorporate neon into her work and

went to a local sign company to inquire if they would teach her. "They

said, 'NO you can't learn this,' "but one man there gave me a couple

of scrap neon tubes, drew me a little diagram of how to hook them up to a

transformer, and told where I could buy a transformer. One neon tube was a

white heart, the other was the word CHOCOLATE. I incorporated them into a

couple of Plexiglas sculptures and after that started drawing my own designs

and having them made by a neon tubebender.

After graduating from Pratt Institute, Lakich moved to San Francisco

briefly before settling in Los Angeles in 1968. "When I was in San Francisco,

I didn't have a single idea. The city was too Victorian for me. When I came

to Los Angeles with all its lights and visual clutter, I suddenly had lots

of ideas."

Lakich began exhibiting neon sculpture in 1973 at Gallery

707 on La Cienega Blvd. Her first solo exhibition, at Womanspace in The Woman's

Building in 1974, garnered a review in Artforum magazine by Peter Plagens

where he commented "...the whole show is solid, however, I doubt whether

Lakich will confine her deveolpment to static, confined neon, if for no other

reason than the recent liberation of electric lights through Process, video,

and performance art." (Boy, was he wrong. Thirty years later, Lakich

has become one of the premier artists in the world working in illuminated

sculpture).

©