Installation

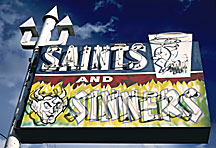

view, Sirens and Other Neon Seductions,

Art Galleries, California State University, Northridge, California

February 17–March 31. 2001

LILI

LAKICH: Sirens &

Other

Neon Seductions

Catalog

essay by Louise Lewis

In

a dazzling array of light, the CSUN Art Galleries discard the last vestiges

of the 1994 earthquake and celebrate their physical rebirth in new facilities

with Lili Lakich: Sirens & Other Neon Seductions.

The artist's invigorating and provocative imagery acclaims the architectural

setting of the exhibition with both individual works and her premier installation

piece, Sirens.

In paying tribute to Lakich, whose work has helped

keep neon sculpture alive in the art world without divorcing it from its populist

origins, the CSUN Art Galleries also herald her move into the realm of installation

art. A genre that is enjoying considerable popularity at the turn of the twenty-first

century, installation art forces reconsideration of both the artist's and

museum's utilization of architectural space and their re-vision of art/life.

Life one hundred years ago, at the beginning of the

twentieth century, was characterized by the phenomenal growth of urban populations,

consumerism, and leisure time, enhanced by the continued advances of the machine

age. The addition of electricity to the urban grid increased the range of

nightlife activities and enhanced a city's magnetism. In 1912 the Frenchman

Georges Claude invented a process to utilize neon (from the Greek word for

new) as a versatile lighting alternative to Edison's incandescent light, originally

seeing it solely as architectural embellishment. His partners convinced him

of neon's potential for advertising signage, and soon Claude had a virtual

monopoly on neon produced in Europe and abroad. In 1923 neon was introduced

in the United States by a Los Angeles car dealership, and soon thereafter

became the American medium of choice for municipal outdoor advertising.

Neon enjoyed its heyday in this country

from the thirties to just after World War II. The surplus of electrical power

allowed extravagant displays of kinetic imagery to enliven commercial and

entertainment districts of major urban centers, as well as small town oases

dotting the desolate stretches of the American Plains and Southwest. Just

after mid-century, however, neon lost favor to plastic and fluorescent signs

and did not see a resurgence until artists such as Chryssa, Martial Rayssé,

Keith Sonnier, Bruce Nauman and others introduced it to the world of art.

Lili Lakich created her first light sculpture, a

self-portrait with lighted teardrop, in 1966, while she was a student at Pratt

Institute in Brooklyn, New York. At the time artists such as Chryssa and Rayssé

were exhibiting their pioneering works in neon in New York galleries, and

influenced by their example, Lakich opted to work in this still experimental

art medium.

Lakich moved from New York to San Francisco, and

ultimately settled in Los Angeles in 1968. In this city, site of the first

American neon sign, Lakich was to bestow another hallmark in neon history

when she co-founded with Richard Jenkins the Museum of Neon Art (MONA) in

1981, dedicated to both the preservation of historic signs and the exhibition

of contemporary neon sculpture. At this time she enjoyed tangible success

with experimental works of her own for exhibition and with commissions for

private collectors and business enterprises. Throughout her career, Lakich

has maintained this tenuous balance between “high” and “low”

art, never losing her attraction to popular and even garish signs enjoyed

since her childhood, while simultaneously exploring the conceptual possibilities

of neon in combination with metal sculpture.

The vital alliance between vernacular

and vanguard applications of neon in Lakich's mixed media sculpture is one

of several recurring themes in her work. Others are autobiographical references

to her nighttime travels across this country and in Europe with the corollary

interest in environmental spaces, the emotional tolls and rewards of personal

relationships, thematic variations of international art historical masterpieces

(African masks, Byzantine icons, Japanese woodblocks, Italian Renaissance

and Modernist paintings), and a witty, sometimes acerbic, tone in her social

commentary.

The artist's first major sculptures were large wall

reliefs, neon drawings on heavy black metal supports. Utilizing popular symbols

such as military insignia, product logos, and tattoo designs, these reliefs

reflect influences of popular signage with their bright and glossy aura. In

Scar (1974) the panther

is borrowed from an embroidered army patch, the skull and cross bones by a

tattoo pattern, and the blood drops by the sperm border of Edvard Munch’s

Madonna (1895-1902). Similarly, Blessed

Oblivion (1975) mimics a tattoo emblem of a panther entwined

by a python, with the whimsical addition of a neon vase to complete the spatial

arrangement. In a more psychological tone Love

in Vain (1977) contains a photographic enlargement of

a heroin addict from Life magazine, altered with dissonant neon lines to become

the tortured form of female-as-chair in a private hell.

Finding the large metal frames a difficult format

to transport and install, Lakich began working in smaller formats, initially

keeping metal as the support backing. Her series on European art icons, specifically,

Mona (1981) after Leonardo,

Venus (1983) after

Botticelli, and Woman in Film

(1989) after an unsigned engraving from the Pre-Raphaelite School maintained

the rectangular format of the originals, but jolted the imagery into a new

world of flash and electric color.

When she discovered the versatility

of honeycomb aluminum, Lakich broke from the rectangular format of earlier

works and extended her range with a variety of sculptural shapes. The appropriation

of widely recognized art images takes a much more experimental turn with her

Icons series, in which honeycomb aluminum serves as the sculptural matrix

upon which neon lines create faces evocative at the same time of Western and

non-Western sources. Holy Ghost

(1983) utilizes the reductionist lines and geometric shapes of one of Jawlensky

's constructivist heads. Saving Grace II

(1984) reverses the aluminum base of Holy

Ghost, incorporates more colored neon, and inserts an

electrical conduit to suggest the crown of thorns of Christ, borrowing from

the richness of the Byzantine religious imagery of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Inspired by masks from the Ivory Coast and Mali, Mambo

(1992) overlays the same aluminum head base with highly ornate and abstracted

shapes denoting facial features.

Icons of more recent vintage, that is, products of

the mass media, are the subject of Lakich’s sculptural homage to rock

and roll. Chuck Berry is venerated in The

Ghost of Rock ‘n’ Roll (1987), a variation

on a Japanese print by Toyokuni, and a publicity photograph of the music great,

amplified with the addition of an actual guitar. Elvis

II (1988) harks back to the era of the fifties and sixties

with boomerang shapes, crackle neon tube, vibrant wavy lines and the King's

trademark stance. The spectacle of these media icons with their stringed instruments

brings to mind the ingenious neon violins and pianos “played”

by chorines in Busby Berkeley's Goldiggers of 1933, one of the earliest

uses of neon in a Hollywood extravaganza.

In contrast to the more public images of the Icons, the

Portrait series affirms Lakich's introspective nature. In visual tributes

to lovers in her past, Lakich reveals unique traits of each person. With

The Warrior: Portrait of Robin Tyler (1980)

Tyler's spare, multi-hued profile floated on a rectangular copper base echoes

the strength seen in a cigar box adaption of an Amerindian chieftain.

Donna Impaled as a Constellation (1983;

drawing, 1982) is a bittersweet interpretation of the subject's interest in

cosmology; the diagonal figural silhouette is pierced with straight and curved

glass lines suggesting an ephemeral stellar outline. Mary Carter is the subject

of two portrait studies in this exhibition: Requiem

II (1988) is strongly metaphoric, portraying a Christ

figure with crown of thorns and chest wound, and suggesting the religious

preoccupations of this long-term companion of the artist. Sweetheart

(1993), also a half-torso figure, is a sculptural valentine, its curves, bold

patterns, bright colors, and pose reminiscent of one of Henri Matisse's nude

cutouts.

The AIDS series underscores Lakich's

humanitarian and activist involvement through her art. In her essay on the

responsibility of artists to society, Martha Rosler states, “The immediacy

of AIDS activism and its evident relevance to all levels of the art world,

including museum staff, brought politicized art far more deeply into the art

world than, for example, earlier feminist activism had.”1

Chryssa

Fragments for Gates to Times Square II, 1966, programmed neon/plexiglass

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York